The Beaver Wars: Iroquois Empire

Part Four of War in the Old Northwest, and Part Three of the Beaver Wars

The last article on the Beaver Wars ended with the dispersal of the Huron in 1649. But the Wars lasted until 1701. So what did the Iroquois do in those fifty-two years? They went west. And east. And north. And south.

A note: fifty-two years is a lot to cover. And details are scarce. Remember, most of what we know about this time period comes from the records of French explorers and settlers. The Iroquois didn't have their own historians writing their side of the story as the Iroquois didn't have a writing system. Likewise, the other Native peoples involved didn't have a writing system. They did all have oral history records—but those are hard to preserve when smallpox is sweeping through a village, killing many. As far as secondary resources go, the Beaver Wars are hardly mentioned. Indeed, if you search “Beaver Wars” on Amazon, the first result is a work of historical fiction. The second is a scenario book for a war game. The third is a history book—about the fur trade from 1765-1840. The fourth is a sequel to the third book, and the fifth is about the World War One Austro-Hungarian General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf.

Nevertheless, here’s what I found about the latter half of the Beaver Wars.

Onward into Ontario and Ohio

The Iroquois attacked Attawandaron, or Neutral Confederacy, in 1651. The Neutral lived in modern-day Ontario, Canada, especially in the Niagara peninsula. They got their name because they stayed out of the Huron-Iroquois wars. The Iroquois attack destroyed them as a nation, and they soon vanished from history.

The Erie, who as you might expect, lived on the south side of Lake Erie, were the Iroquois next target. The Erie, too, were destroyed as a nation. Like the Huron and Neutrals and other tribes dispersed by the Iroquois, survivors either got captured by the Iroquois or fled to other tribes.

France Fights Back

Meanwhile, fighting continued between the Iroquois and the French and their native allies. Iroquois raids not only meant the loss of colonists, it meant the loss of fur. And without fur, why would anyone stay in “[a] few acres of snow,” as Voltaire latter described Canada.

Rather than hop on the next ship to France, the French settlers counterattacked in 1660. Captain Adam Dollard, Sieur des Ormeaux, led fifty-eight men, including forty-two native warriors, on a mission to intercept an Iroquois fur shipment. The plan didn't survive contact with the enemy. Dollard’s men ambushed a scout party of Iroquois, then got attacked by a larger Iroquois force. Dollard led his men to an abandoned fort, where they were besieged by two hundred, then up to seven hundred, Iroquois warriors. All of Dollard’s native allies, save chief Huron Annahotaha, left him. Of those that left, only five made it back home. The rest were killed by the Iroquois. After five days, all the French were dead, too. Whether because the Iroquois had enough scalps or had enough casualties, the war party abandoned its original plan of attacking Montreal and went home, and the fur once again flowed to the French.

Today, Dollard is a hero in Canada, and the Battle of Long Sault is something of an Alamo moment in Canadian history.

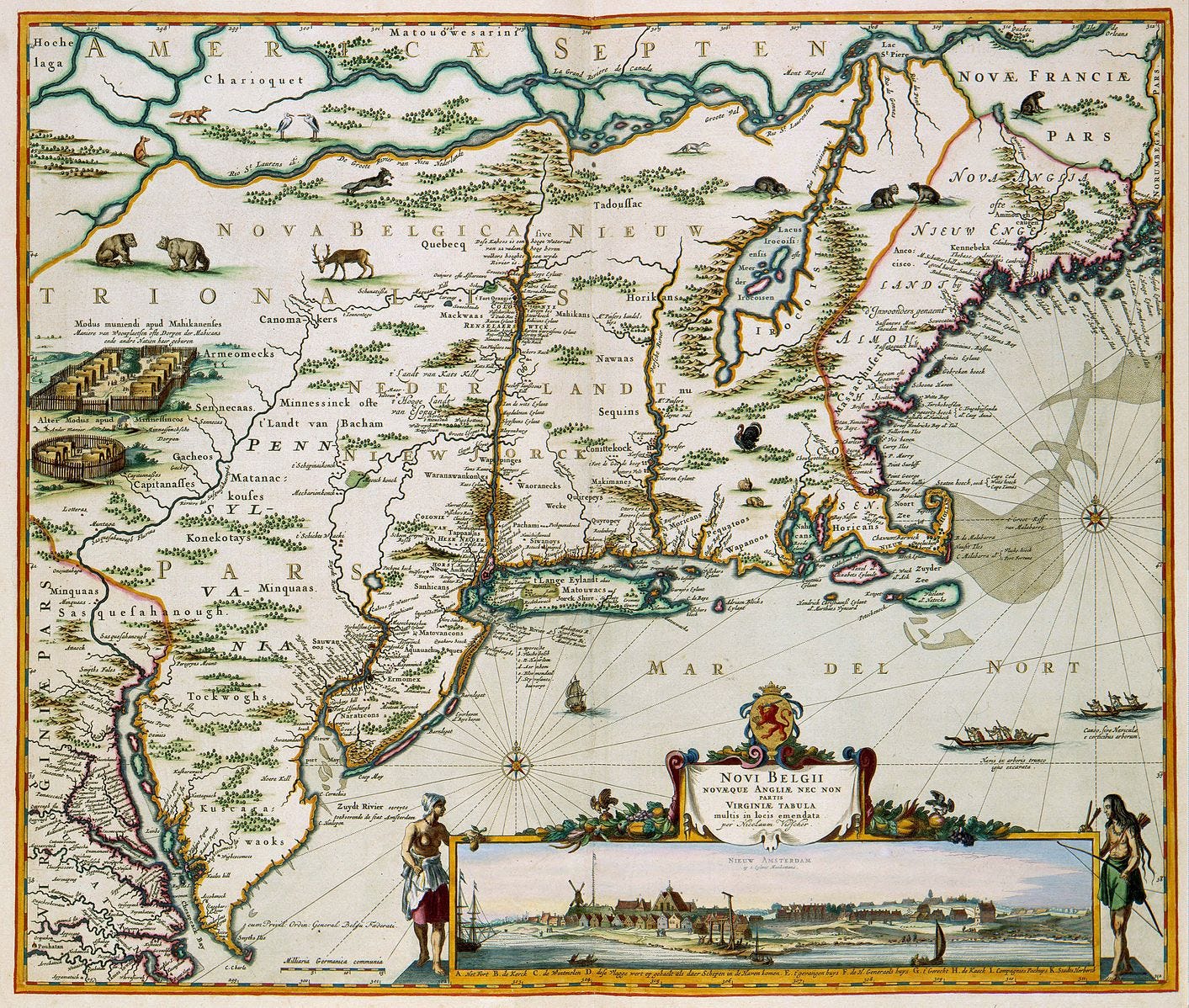

In 1664, the Dutch colony of New Netherland (modern-day Southeast New York, as well as parts of surrounding states) fell to the British. Remember, it was the Dutch who supplied the Iroquois with guns. The Cayuga, Onondaga, Seneca, and other tribes of the Iroquois made peace with the French. The Mohawk and Oneida tribes remained at war with the French.

In 1665, Carignan-Salières Regiment arrived in Canada from France. Those regular soldiers, which numbered six hundred, along with local militia, attacked the Mohawk in 1666—in January. As you might imagine, fighting a war in the Canadian/New York winter is a bad idea. Some historians might even call it the worst thing an army could do, short of invading Russia or Afghanistan any time of the year.1 Sixty men froze to death. The rest turned back. The Regiment went out again in September of that year. They reached Mohawk villages but found no one at home. The Iroquois had figured why fight men with guns when you can escape. The French burned the villages and left. In 1667, the Mohawk and Oneida made peace with the French.

But that wasn’t the end of the Iroquois’ expansion.

Westward, Ho!

About the year 1670… they acquired possession of the whole country between lakes Huron, Erie, and Ontario, and of the north bank of the St. Lawrence, to the mouth of the Otawas river, near Montreal.

League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee or Iroquois by Lewis Henry Morgan

The Iroquois were blocked in the north, but they still had three directions to expand in. And expand in each of those directions they did. From modern-day New England, to South Carolina, to Illinois, the Iroquois fought and conquered. I’ll skip over the fighting in New England and in the South, and focus on the events in the Old Northwest.

War parties of the League also made irruptions [sic] into the country of the Miamis, others penetrated into the peninsula of Michigan, and still others were seen upon the distant shores of [L]ake Superior. No distant solitude or rugged fastness was too obscure or difficult to escape their visitation; no enterprise was too perilous, no fatigue too great for their courage and endurance.

League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee or Iroquois by Lewis Henry Morgan

The Miamis are also known as the Myaamiaki, and call themselves Myaamia, “Downstream People.” They lived in what’s now northern Indiana, southern Michigan, and western Ohio. In Stories of Indiana by Maurice Thompson, this is said about Iroquois Miamis relations:

The Iroquois Indians were the inveterate enemies of the Miamis, and often entered their territory to make war upon them.

The books then says:

In the year 1680 a notable fight took place between two large companies of these tribes. The Miamis were hunting in the region of St. Joseph River when they were surprised by an army of Iroquois, who defeated them with great slaughter and carried off about three hundred of their women and children. …

But that was not the end of the story. The Miamis were determined to get their families back. The Miamis went ahead of the Iroquois and set up an ambush. Then,

With their bows and arrows held ready for instant use, they crouched in the tall grass of a prairie and waited. On came the happy and proud Iroquois, marching at ease, not dreaming of danger, when suddenly, out of the silent, motionless grass whizzed a flight of deadly missiles, volley after volley in rapid succession, and with murderous effect. The Miamis did not cease shooting until their quivers were empty. Then, shouting the war cry, they flung aside their bows, leaped forth from the grass, club in hand, and charged. It was a close and terrible fight, but the desperate Miamis won, and so retook their families, besides capturing all the arms of the Iroquois.

Stories of Indiana by Maurice Thompson

Oddly, according to Thompson, the French gave the Iroquois their guns.

In September, 1681, another band of Iroquois approached a French fort near what’s now Rock Fort, Illinois. There was no fighting.

But peace between the French and Iroquois wouldn't last long…

Enter the English

The French and Iroquois went to war. Again. More French soldiers arrived in 1683. In 1684, Governor of Canada Joseph-Antoine le Fèbvre, sieur de La Barre invaded Iroquois territory. After his men faced sickness and starvation, La Barre meet with Chief Garangula. La Barre made peace. The Iroquois got the better bargain.

Meanwhile, the English had started selling guns to the Iroquois. But the English didn't stop there: they made an alliance with the Iroquois against the French.

England and France had been fighting wars, off and on, since the middle ages. In 1689, the two nations went to war again. But their colonies in North America started fighting in 1688. This was King William's War (also called Castin's War, Father Baudoin's War, the First Intercolonial War, or the Second Indian War.) King William’s War was part of the larger Nine Years' War, just as the latter French and Indian War was part of the Seven Years War.2

I’m going to be brief in writing about King William’s War. One, because most of the fighting took place in New England, eastern Canada, and Hudsons Bay, and two, for the sake of time. If you're curious about King William’s War, or about anything else mentioned in this article, I encourage you to do your own research. (See the Sources and Further Reading section below.)

The fighting started in Maine3 with raids and skirmishes. One side would attack, then the other would retaliate. And so on, and so on.

On August 5, 1689, the Mohawk warriors committed the Lachine massacre in Quebec. Twenty-four French died, as did three Mohawks.

In 1690, New Englanders looted Port Royal (present-day Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia) after the French surrendered.

The war went on: battles, skirmishes, raids, massacres.

On September 20, 1697, the Peace of Ryswick ended King William’s War. Nothing changed in North America.

But the Beaver Wars went on…

The End of the War is Near…

The Iroquois (and other Native tribes) weren’t invited to Ryswick to negotiate with the European powers, so they still had to deal with France.

The French invaded Iroquois territory in 1692-3 and 1696. Both invasions left Iroquois villages and crops devastated. The 1692-3 invasion also took three hundred captives.

Those attacks, and the growth of the English colonies, led the Iroquois to make peace. (If you're wondering why the Iroquois would be worried about the English since the English were their allies, remember that the Wampanoag had a treaty with the Pilgrims—which eventually ended.)

The Great Peace of Montreal

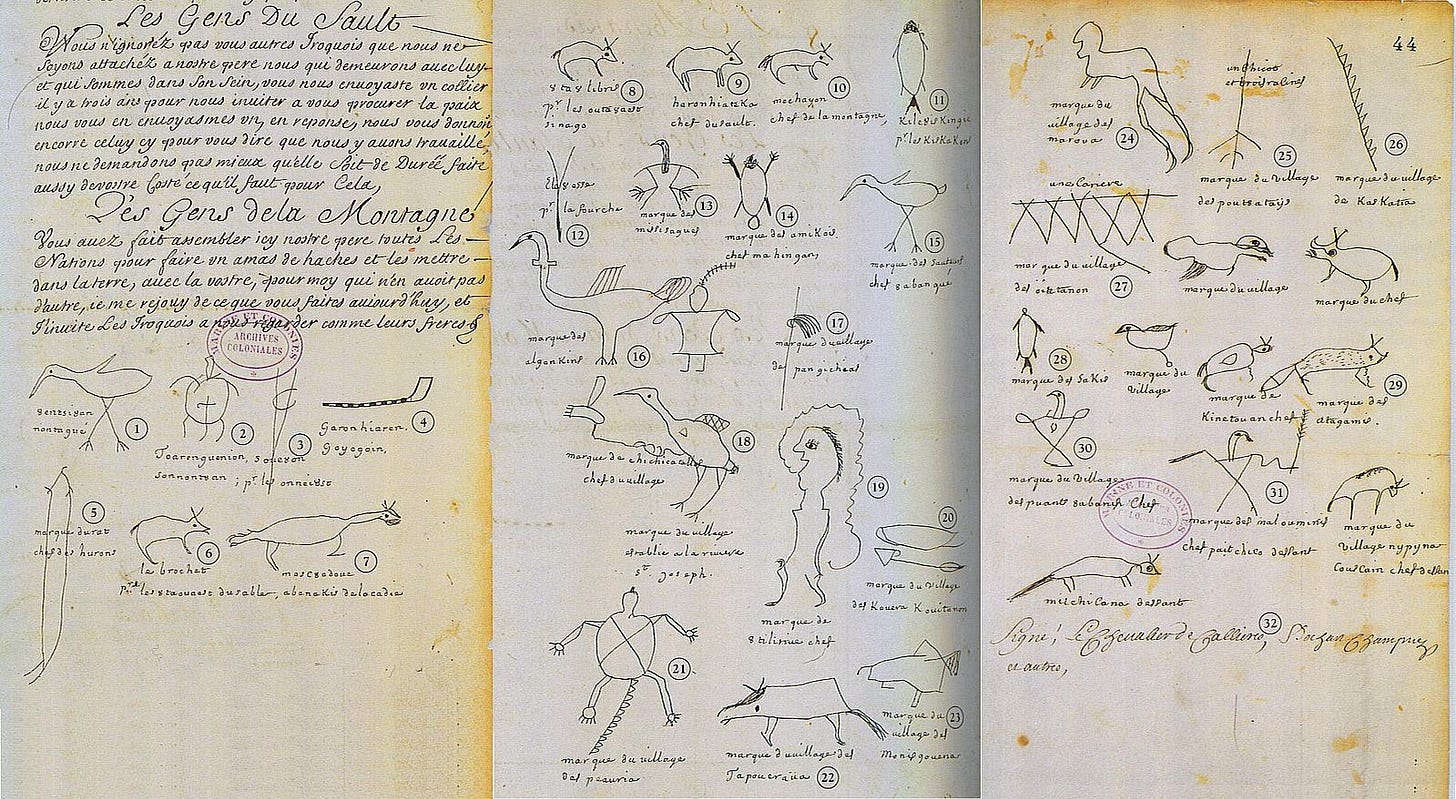

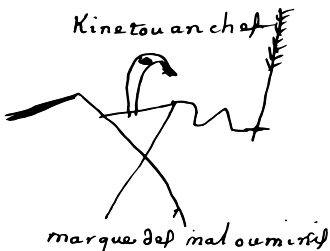

Negotiations between the French and Iroquois started in 1698, but it wasnt’t until 1700 that the first agreement was reached. Then, in 1701, chiefs from the thirty-nine tribes met in Montreal, Canada, to sign a peace between themselves and the French. All five tribes of the Iroquois (Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca), Miami, Odawa, and Ojibwe were among those that came. After debating the terms of the peace, the representatives signed the Great Peace on August 4, 1701.

As you can in the picture above, the tribal representatives used pictures rather then a “normal” signature. Here are some of them up close:

And with that, so ends the articles on the Beaver Wars. But this isn’t the last time we’ll hear about these tribes, or about fighting between England and France over North America. In fact, the next war covered will be fought on a larger scale…

But when will it be covered? Probably not until late August or early September. See, I moved to New Mexico for an internship, and the summer will be PACKED. If I get a chance to research/write, I will. But like I said, summer will be PACKED. But once I’m less busy, War in the Old Northwest will resume, as will Henry Ford.

Sources and Further Reading

League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee or Iroquois by Lewis Henry Morgan

Stories of Indiana by Maurice Thompson

History of Michigan, From its Earliest Colonization to the Present Time by James H. Lanman

The Border Wars of New England: Commonly Called King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars by Samuel Adams Drake

The Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum: Battle of Long Sault: 2-10 May 1660

Parks Canada: Fight at the Long-Sault National Historic Event

Okay, by some historians, I mean me, the author. And only me, the author. But really, attacking in January was dumb.

The French and Indian War will almost certainly be covered in the next War in the Old Northwest article.

Which was then part of the Dominion of New England. During the war, it became part of the Province of Massachusetts Bay.

1. Actually, winter attacks have across history often made good practical and tactical sense. In deep winter when it's cold enough, the ground is hard again rather than muddy so you can travel more easily. It's also more likely that you will find your enemy huddled around their fires rather than scattered around during whatever chores and tasks they regularly have to complete. This was true on the Russian Front in World War Two and it was also true at Glen Coe in Scotland in 1692. However, if you are not prepared and equipped to travel in winter regardless of conditions because you really don't want to be caught in a winter blizzard - then it's not a good idea and you should stay close to your own fires but put out reliable sentries perhaps.

Wow, those tribal chief signatures are so interesting. I notice there's slight differences between a few of the cows(?), but I wonder if there was ever the possibility of signatures getting confused.